A guy who hates himself walks into a party

A subjective deep-dive into men who hate themselves and the delusion of romanticising them

There is a certain kind of man who turns his self-loathing into foreplay.

You learn to recognise him the way you recognise a recurring dream—confusing at first, then eerily familiar. He’ll tell you I’m broken like it’s a profound confession, when really it’s a seductive move. He believes that naming his damage makes him deep, and that being deep makes him desirable.

He treats his self-hatred not as a flaw, but as a kind of romantic currency—a sad, sexy bartering chip. He offers it up to women in exchange for closeness, for forgiveness, for being understood.

Ultimately, this certain kind of man expects to be loved in the same way he loathes himself: completely, irrationally, unflinchingly.

I met one of these men last weekend, at a party I crashed.

A WOMAN WHO JUST THREW UP AND A GUY WHO HATES HIMSELF WALK INTO A PARTY

It is eleven o’clock on a Saturday and I am at a party.

I am also drunk. All night, I have been choking down drink after drink: glasses of weird natural wine and too-strong Negronis and, now, margaritas rimmed with salt openly stolen from the open bar.

I am not supposed to be at this party because, frankly, I was not invited. I am only here because of some strange kind of fate.

And I call it that—“fate”, the strange kind, at least—because there’d been a man at the party. I know him. Unlike me, he was supposed to be here. I did not know he was supposed to be here.

I am sad because the man has left the party. He did not say goodbye.

(I do not blame him for leaving, though, because the man has a lot on his mind. I know this because he told me some of the things on his mind the night before, when we ate dinner together.)

Because I am drunk and sad and not supposed to be at this party, I go into the stairwell and call the man who did not say goodbye. I say things like “Why did you go?” or “I didn’t think you’d leave.”

(I say other things, too, probably—things probably less innocent or kind or normal, but I do not remember them—which is to say: the conversation does not go well.)

The man hangs up on me and I begin to cry. I leave the party to smoke a cigarette outside. I throw up. I feel pathetic. I go back inside and stand in the stairwell.

This is when the other man finds me—not the one I know, the one who did not say goodbye, the one who has just hung up on me. A different one. The one I mentioned earlier. The one who is member of the group that is the certain kind of man who turns his self-loathing into foreplay.

Though this other man does not know me, he is smiling at me like he does.

“I wish I was the man on the other side of the phone,” the other man says.

I want to say, And what the fuck is that supposed to mean? but I do not say anything. Instead, I blink at him, waiting for context.

Finally, he delivers it.

“I saw you on the phone, crying in the stairwell. Then I saw you throw up. And I thought to myself, ‘I want to be the man who makes her cry in a stairwell and throw up after.’”

There is a long pause. I let it linger. He stares at me. Because I do not know what else to do, I laugh nervously. He shrugs.

“I guess I like it when women are heartbroken.”

When I tell him I am not heartbroken, he laughs.

“Sure, tell yourself that.”

And then:

“It’s nice to know women hate themselves, too.”

I take a step back. I feel my shoulder blades graze the wall behind me. I’m trapped. Fuck.

“Sorry—do you hate yourself?” I ask him.

He looks at me, puzzled.

“Of course I do,” the other man says. “Every man does.”

I draw in a sharp breath. Give me a break, I want to say.

“You should work on that,” I tell him instead.

He smirks at me.

“Yeah, you say that, but, you know… women like you typically find self-loathing to be quite sexy.”

I want to tell him I’m disgusted. I want to tell him he needs to get a fucking grip. But instead, I just stand there, quiet and a little too still, as if the air has turned to glass and, if I move, will shatter and cut me.

To be clear, it’s not that what this other man said surprised me. I’ve heard it before. Well, maybe not as explicitly—but the sentiment, the performance, the hunger for witness?

I’ve felt it. I’ve seen it. I’ve lived it.

GENTLY MYTH BUSTING SOME MYTHS OF MODERN MASCULINITY

One of the greatest myths of modern masculinity is that self-loathing is a form of depth. That hating oneself is the purest form of evidence that one is a “thinker,” or, at least, that one has had at least one deep thought about the world.

Another myth of modern masculinity is that if a man admits to being broken, then it must mean they are safe. Real. Good. Probably kind. And, because they have told you this and you have not run away, it must mean that you are maybe even someone worth loving as much as you love them.

It is a myth perpetuated by specific factions of both sexes: firstly by the men who have confused interiority with insight—who believe that the simple act of being able to name their pain makes them emotionally fluent. And secondly by the women who, for too long, have been told that the best way to earn love is to not only understand suffering, but to tend to it.

THE ULTIMATE MALE FANTASY IS THAT OPENLY HATING THEMSELVES MAKES THEM SEXY AND NOT FUCKING WEIRD

The other man at the party was not the first man I’ve met who believed his self-hatred made him interesting. He was just the first one to say it out loud.

Most of them—the men who tell you they hate themselves—are more subtle. They say things like I’m not good at this or I don’t know how to be with someone right now.

(Of course, they do not do this before they kiss you or fuck you or not before they fuck you or look you in the eye and tell you you’re “a completely gorgeous angel who doesn’t deserve a man like me, so thank you for being here.”)

The thing about self-loathing men is that they want you to feel special. That’s what makes them so enticing.

They do not want you to feel special because they are particularly interested in making you feel good—really, it’s because they have deigned you worthy of witnessing their brokenness. They want you to be happy when they show you their cracked brains. They want you to look at the mess inside them and see it as something beautiful instead of what it really is: pain that is usually as unexamined as it is unremarkable.

That’s the fantasy of male self-loathing. And it’s one which allows them—the self-hating man—to be loved without the responsibility of being better.

A CERTAIN KIND OF WOMAN, PT. I

There is a certain kind of woman who has been taught to register damage as depth.

She knows how to be empathetic before she knows how to be angry. She was raised to believe that love means staying. That love means patience. That love means work. She thinks that being “good” at love means being good at understanding someone—and that understanding someone means staying, even when it hurts. Especially when it hurts.

She is the kind of woman who, yes, wants to be chosen, but more than that, she is the kind of woman who wants to be needed. She wants to be the one who “gets it.” The one who sees what no one else sees. She’s been told that this makes her strong, but also told it makes her a little bit dangerous, and somewhere along the way she began to believe that being wanted for her empathy was just as good as being wanted for herself.

And when a man turns to her and says I hate myself—what she hears is I trust you, Please fix me, Stay.

So she trusts and fixes and stays. Of course she stays.

A CERTAIN KIND OF WOMAN, PT. II

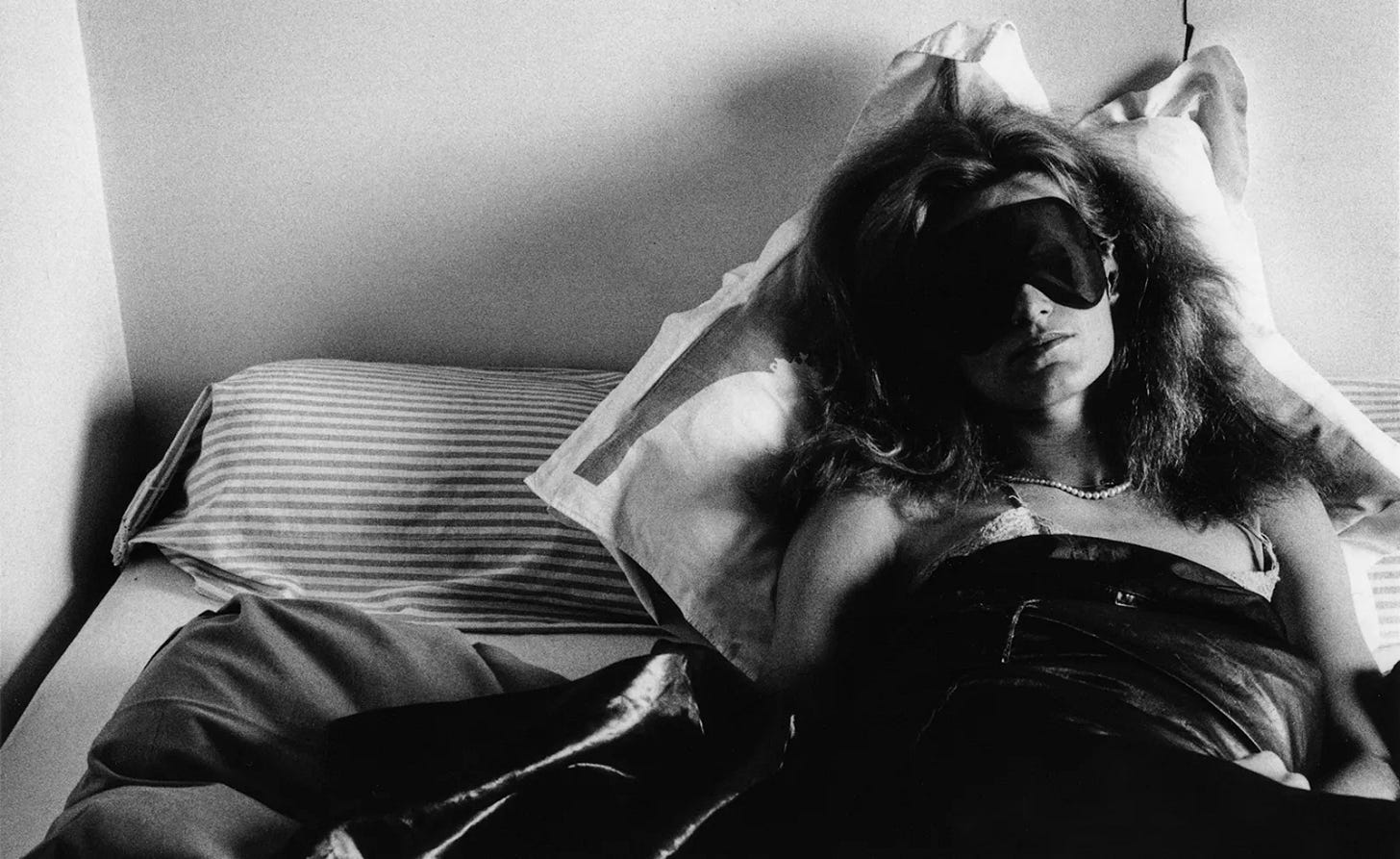

Maybe the other man at the party was right—this certain kind of woman does believe the self-loathing is sexy, at least a little. The cracked interior, the vague melancholy, the sadness he never quite names—it’s all a bit erotic.

And she likely believes this because, since girlhood, she’s been taught that when it comes to loving a man, her job is to make him better—or at the very least, to make her love for him worth it because she sees in him not brokenness, but potential.

And when he eventually pulls away—when he tells her she deserves someone better, when he disappears into his self-hatred, when he says it’s not you, it’s me and it’s complicated and I just need time—she’ll just nod. She’ll tell him she understands. And, to the self-loathing man, she is the certain kind of woman who always understands, even when she so totally does not.

(That’s the real trick of male self-loathing—it will make this certain kind of woman feel like a mirror whose gazer blames it for reflecting.)

But, after a little while, after he’s left or she’s moved on, in the hazy future when this certain kind of woman is in the bath or writing in her journal or slumped in a cab at two o’clock in the morning on the way home from a party to which she wasn’t invited, she’ll wonder: What was I even doing there? Was I even in love with him? Did he even hate himself?

And, because it’ll be difficult to come up with answers to these questions, she’ll ask another: Even if I knew, and I was, and he did—why did I try so hard to make him hate himself less?

THE RESENTMENT

The problem with loving a man who hates himself is that he will eventually hate you, too.

(Okay, maybe not hate—hate is a strong word. Perhaps it is kinder—maybe even truer—to say that he will eventually come to resent you instead.)

He won’t resent because you failed him. No, he will resent you because you didn’t. Because you stayed. Because you loved him anyway. Because you saw all the ugly, unresolved, jagged parts of him and said: Okay. I can hold this.

And holding it—or, at least, being willing to hold it—is something for which he cannot forgive you, because on some level, he doesn’t believe he is worth it—love, that is. And not just your love—it’s anyone’s.

So, the self-loathing man thinks, if she wants to stay here with me even though I hate myself, there must be something wrong with her, too.

WHAT THE SELF-LOATHING MAN SAYS HE WANTS AND WHAT HE SAYS INSTEAD

Self-loathing men believe that hating themselves keeps them safe. That it keeps them special. That it keeps them just out of reach.

And they think this because they also believe that it is easier to be tragic than accountable. Easier to be a poem than a person. Easier to be the one who left than the one who tried.

Still, in theory, the self-loathing man wants to be understood. But in practise, when you understand him—when you really see him, when you know how the wound was inflicted, when you’ve watched it split open and bleed and fester, when you’ve stitched it closed again with your concern, your tenderness, your laughter and sex and time—he doesn’t feel grateful. He feels exposed.

And it is then—the moment he realises he is cold and naked and defenceless—when the self-loathing man will tell you he hates himself. He will tell you you’re too good for him. He will say these things like an apology. But it’s not. It’s a punishment.

Because in his logic, the only person worth loving is someone who would never stay.

And you stayed.

THE TRAGEDY OF THE SELF-LOATHING MAN

The tragedy of the self-loathing man is not that he hates himself. It’s that he makes it everyone else’s (i.e., women’s, mostly) problem.

He says he wants to be understood, but what he really wants is to be worshipped for staying broken. To be admired even when he feels he cannot try.

And the tragedy of the women who love them—the ones who stay, who stitch, who reflect—is that we think understanding is the same thing as being loved.

But it’s not. It never was.

FEAR AND SELF-LOATHING

I don’t know why I stayed talking to the other man at the party. Maybe I was curious. Maybe I was too lonely to move. Or maybe I just didn’t want to think about the man I knew and saw and called and cried over. The man I still miss. The man I still care about.

Maybe, though, I stayed because I recognised him, the other man. Not as a person, but as a pattern. A paradigm. A human-shaped story with floppy hair and a swivelling jaw whose ending I already knew.

When I think about the other man and the other men like him—the ones who hate themselves out loud and expect you to call it sexy or deep or, if it gets there, love—I wonder if it’s even self-loathing at all.

Or if it’s just fear.

As in: the fear of being chosen. Of being known. Of having nowhere to hide once someone sees the wound and doesn’t look away even when he knows they could.

This essay is a work-in-progress chapter in my forthcoming book of essays, Easily Incorrect. Thank you so much for reading it! Love you <3

P.S. THERE ARE OVER 1,000 OF YOU HERE!!!! UHHHH, WOW! THANK YOU SO MUCH FOR READING, COMMENTING, AND JUST SUPPORTING MY WORK—I AM SO, SO HONOURED AND, FRANKLY, FLABBERGASTED.

I think David Foster Wallace said something like “there’s a lot of narcissism in self hatred”

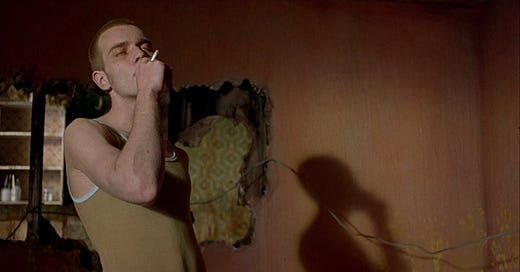

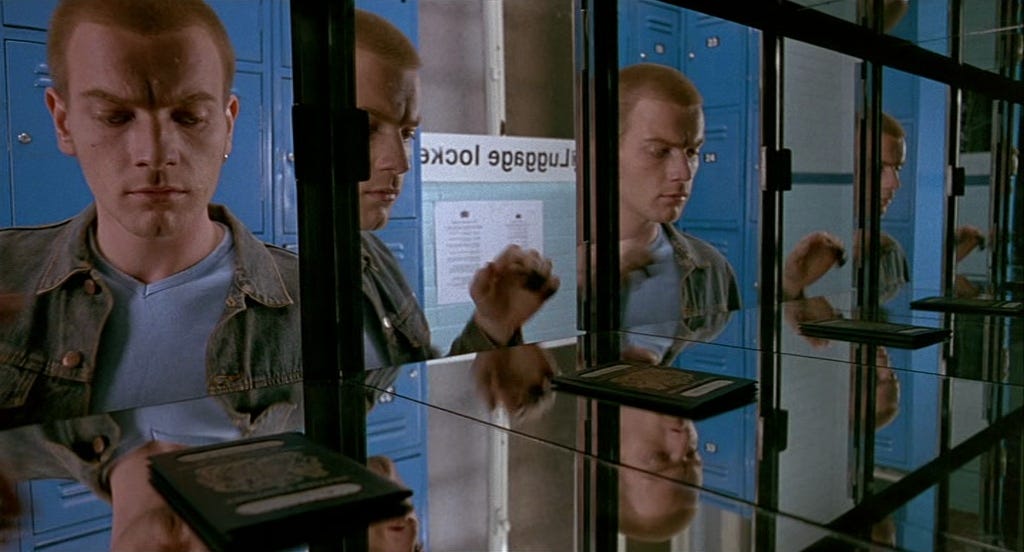

Bro what did Trainspotting do to you